The Brothers Karamazov

The Wrap Continues

with Dennis Abrams

From Harold Bloom (probably my favorite literary critic) — Genius

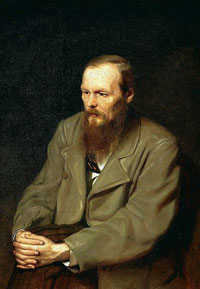

“Sigmund Freud, rather polemically, placed The Brothers Karamazov first among all novels ever written, approaching Shakespeare in aesthetic eminence. The judgment was excessive, but the book certainly is the strongest that Dostoevsky composed, and it is where his genius should be sought. It is his final work and his intended revelation, published a year before his death at fifty-nine. His only son, Alyosha, had died at the age of three in 1878, which is prelude to The Brothers Karamazov, whose hero is Alyosha, the youngest brother. Had Dostoevsky lived, there would have been a second volume in the novel, centering almost wholly upon the fully mature Alyosha.

But we have only The Brothers Karamazov in one substantial novel of seven hundred and seventy-six pages…Most readers regard the novel’s protagonist as being either Dmitri, poetic sufferer, or Ivan, prideful intellectual, or both together, rather than the realistic and loving Alyosha. The book’s glory is that we are fascinated by all three brothers (despite Dostoevsky’s palpable dislike for Ivan) as we also are enchanted by their dreadful father, the vitalistic monster Fyodor Pavlovich, and interestingly are repelled by their bastard brother, the cook Smerdyakov. These five Karamazovs are the genius of the novel; the principle women, Grushenka and Katerina Ivanovna, seem to me to divide male fantasy between them, and they fail to persuade as personalities. Tolstoy could create women; Dostoevsky could not, though he studied Shakespeare, hoping to learn the secret.

To invoke the genre of the novel does not help much in reading The Brothers Karamazov. We might call it Scripture, though that would be too broad a designation, since Dostoevsky seems to combine the Book of Job with the Revelation of Saint John the Divine, with much of the rest of the Bible implied. Critics, following Mikhail Bakhtin, speak of the novel as a polyphony, but why that applies more to it than to Dickens or Proust is unclear to me. There is a peculiar narrator, who seems to represent the public in general, though Dostoevsky sometimes breaks in. The Brothers Karamazov could be called gloriously unsteady, which is appropriate for the Old Karamazov and his volatile sons, who in different but parallel ways share in his outrageous nature.

Freud overpraised the novel because it confirmed his theory in Totem and Taboo, where the Primal Father appropriates all the women for himself, and finally is slain by his sons. Hatred of the father, according to Freud, is the source of our unconscious guilt. But, except for Alyosha, all the Karamazov sons explicitly hate their ferocious father, and Alyosha is saved from that hatred only by having found a replacement in the monk, Father Zosima.

It is Mitya’s novel, but Dostoevsky gave his own first name to Old Karamazov (who is actually fifty-five), and the sensual exuberance of this worst of fathers makes us feel his absence after he is murdered by Smerdyakov. Dostoevsky, in his Notebooks, declared that ‘we are all, to the last man, Fyodor Pavloviches,’ since we are all sensualists and nihilists, however we attempt to be otherwise. Dostoevsky, who compelled himself to religious belief, was anything but a mystic, and was the ancestor of Kafka’s passionate motto: ‘No more psychology!’ There are almost no normative personalities among Dostoevsky’s characters: they are what they will to be, and their wills are inconstant. And so is Dostoevsky’s. His unfairness to Ivan is exasperating, but Dostoevsky intends to exasperate us. He certainly would have declined to care about the reactions of Jewish critics, since he himself was a vicious anti-Semite, comparable to Ezra Pound. It is important to remember that Dostoevsky was an obscurantist, and a supporter of Czarist tyranny and Russian Orthodox theocracy. He was a vehement parodist of Westernization, and firmly believed that Russians were the Chosen People and that Christ was the Russian Christ. Admirers of Dostoevsky should read his Diary of a Writer, a fascinating and obnoxious book. It is one thing to be passionate and provocative, and quite another to preach hatred of non-Russians in anticipation of the End of the World.

Dostoevsky’s genius was for dramatizing character and personality, and he seems to me to have a deeper relationship with Shakespeare than criticism so far has revealed. His nihilists are Shakespearean: Svidrigailov, Stavrogin, Ivan Karamazov. And there is something of a Falstaffian parody in Fyodor Karamazov, though I find it distressing. Western literary tradition was not for Dostoevsky the nightmare it constituted for Tolstoy, but I am uncertain that Dostoevsky could see the differences between Shakespeare and the novels of Victor Hugo, whose vision of the wretched of the earth was not far from Dostoevsky’s own.”

More to come tomorrow…

I always say, Harold Bloom should not be taken seriously as a critic, his critical comparative do not basis and his theories undermine their interpretation. Moreover, their fanaticism by Shakespeare is out of joint