Part Two, Chapter One

by Dennis Abrams

Early the next morning: “A terrible chill seized him…he was suddenly stricken with such shivering that his teeth almost flew out and everything in him came loose.” Remembering to put the hook on the door, to examine himself, to hide the purse and things he had taken in a corner low down, “where the wall paper was coming away…” After falling asleep again, he wakes up and begins to frantically tear out the lining of his pocket, to take apart the loop that had held the axe underneath his jacket, the toe of his sock soaked in blood. No matches to light the stove to burn the evidence. He falls asleep again, and wakes up that afternoon to the sound of knocking at his door — Nastasya and the caretaker. A summons from the police. His fever. “It was an ordinary summons from the local police to come to the chief’s office that day at half past nine. ‘But this is unheard of. I’ve never had any personal dealings with the police! And why precisely today?’ he thought, in tormenting bewilderment. ‘Lord, get it over with!’ He fell on his knees to pray, but burst out laughing instead — not at praying, but at himself…’If I’m to perish, let me perish, I don’t care!'” Socks. Laughter giving way to despair. “‘It’s a ruse! They want to lure me there by a ruse and suddenly throw me off with everything,’ he continued to himself, walking out the stairs. ‘The worst of it is that I’m almost delirious…I might blurt out some foolishness.'” Will there be a search while he’s away? “If they ask, maybe I’ll tell them.” The station, “The stairway was narrow, steep, and all covered with swill.” The smell of rancid paint. Two ladies — one in mourning, the other, “an extremely plump and conspicuous woman, with reddish-purple blotches, all too magnificently dressed, and with a brooch the size of a saucer on her bosom…” Raskolnikov’s dizziness. The airless room. The young clear, “about twenty-two years old, with a dark and mobile physiognomy which looked older than its years, fashionably and foppishly dressed, his hair part ed behind, all combed and pomaded, with many rings and signet-rings on his white, brush-scrubbed fingers, and gold chains on his waistcoat. He even spoke a few words of French…” A question of money. Recovery of a one hundred and fifteen rouble note which Raskolnikov gave to his landlady, who gave it turn in payment to the court councillor Chebarov. Relief. Laviza Ivanovan’s story (in a heavily German accented Russian) of her most noble house, and her most unnoble drunken guest. Lieutenant Ilya Petrovich. Chief of Police Nikodim Formich, “Come, come, my friend, poverty is no vice!” Raskolnikov’s defense: His poverty, his love for his landlady’s daughter, her death from typhus, the landlady’s promise never to use the promissory note against him. “Raskolnikov fancied that after his confession the clerk had become more casual and contemptuous with him, but — strangely — he suddenly felt decidedly indifferent to anyone’s possible opinion…And where had these feelings come from? On the contrary, if the room were no suddenly filled not with policemen but with his foremost friends, even then, he thought, he would be unable to find a single human word for them, so empty had his heart suddenly become.” After signing the papers, Raskolnikov felt “as if a nail were being driven into his skull. A strange thought suddenly arose in him: to get up now, go over to Nikodim Fonisch, and tell him all about yesterday, down to the last detail…” Raskolnikov overhears Fomich and Petrovich discussing the murder, gets up to leave and faints. Asked how long he’s been ill, he ends up admitting that he had left his apartment for a walk after 7pm the night of the murder. “‘A search, a search, an immediate search!’ he repeated to himself, hurrying to get home. ‘The villains! They suspect me!” His former fear again came over him entirely, from head to foot.”

—

Fairly self-explanatory, as Raskolnikov’s badly-timed summons to the police station plays on his already nerve-rattled mind. I was struck by (among other things) the stench of everything…the nauseating odor of the paint, the reek of Louisa Ivanovna’s perfume (noted twice in one paragraph) — one gets the constant feeling in this book of the walls closing in, of confinement, of…stench. And the contrast between Raskolnikov’s rags and the foppish clerk…

—

From one of my favorite literary critics, the Washington Post’s Michael Dirda, a nice summary of where we stand so far:

“Crime and Punishment is…a story with a power that burst through any English version. It is also a novel that might easily be set in, say, contemporary Washington, a city as artificial and dream-filled as old St. Petersburg.

A young man of twenty-three has dropped out of school because he can’t pay his tuition. He lives in what amounts to a closet and, being in arrears on his rent, is afraid of running into his landlady. Everywhere he wanders in his ghetto neighborhood people are out on the pavement begging, whoring, or drinking. One pathetic drunk buttonholes him and confesses how he sent his own daughter out on the streets. ‘Do you understand,’ he implores, ‘do you understand, my dear sir, what it means where there is no longer anywhere to go?’ Revolutionary ideas fill the air, and this rather sullen intellectual finds them attractive. Sometimes, though, he thinks of throwing himself into the river.

And why not? His father is long dead. His fervently religious mother has been reduced to taking in sewing to save some money for her son’s ‘university education.’ Even his attractive, hot-tempered young sister has accepted a menial job in a rich household. After narrowly avoiding seduction by the priapic husband, she has recently agreed to marry a considerably older and utterly crass businessman who can hardly wait to get her into bed. Our hero realizes that both his mother and his sister are sacrificing their lives for him.

Now, an old witchlike pawnbroker lives nearby, venal, usurious, and cruel; she treats her own sister like a slave. Why should such an insect flourish while others suffer? Think what could be done with all her money. An ambitious self-starter could finish his law degree, grow wealthy, divert funds back into his community, build parks, relieve the poor and addicted, achieve great things. Surely, the life of a miserable ‘louse’ is next to nothing compared to all these good deeds. ‘One death for hundreds of lives — it’s simple arithmetic.’

And as Dostoevsky’s ambiguous hero Raskolnikov — for it is he, not some kid in a modern big-city slum — feverish, despondent, half sick from malnutrition, starts to toy with the idea of murder, to rehearse it over and over in his mind, but only, he tells himself, as a kind of mental game. Then late one afternoon he inadvertently learns that at 7 PM the next day the old moneylender will be alone.

Will he do it? Should he? Raskolnikov wavers for a moment; then the life of Alyona Ivanova is bludgeoned out of her in a single chilling sentence: ‘The moment he brought the ax down, strength was born in him.’ Shortly thereafter, the pawnbroker’s unfortunate sister returns home early.

Against all odds, Raskolnikov manages to escape the scene of his double murder. He is safe. No one, absolutely no one, can touch him. We are on page 86, end of part 1, and Crime and Punishment has only just begun to accelerate.”

—

Thursday’s Reading: Part 2, Chapters Two and Three

Enjoy.

Hi Dennis, I’m here, reading along with you – as promised. It’s riveting! This is my first time reading C&P and I’m so glad to have this group to read with- thanks. I’m trying not to read too far ahead. The crime scene was harrowing. While I was reading it I was yelling at the book “hurry up, you idiot- Lisveta will be home any second!” I, too, was utterly destroyed by the dream with the horse-beating. In this chapter the quote you’ve posted in exactly the one I highlighted. I’ve had days like that. I love the vivid descriptions of the characters at the police station. The translation of the madame Ivanovna’s “brisk Russian, but with a strong German accent”…”und he had no maniers, no maniers at all….” No maniers indeed.

So when you were yelling at the book…were you hoping Raskolnikov wouldn’t get caught or were you trying to protect Lizaveta?

I was hoping Lizaveta wouldn’t meet the axe. It would be easier to be sympathetic towards Raskolnikov without her murder.

So the question then is this…is there a part of us that agrees that killing the pawnbroker is somehow…justifiable?

Not justifiable, but perhaps purposeful. We can see the thought going into it. We see Raskolnikov thinking about it. Lizaveta was already a victim of her stepsister and instead of being freed by her death, however upsetting it would be to her, she becomes another victim, just because she returned early.

Your question Dennis, brings to mind James Joyce’s cryptic comment about this novel:

“it was a queer title for a book which contained neither crime nor punishment.”

(Richard Ellman’s biography of James Joyce p 485)

Which raises another question: Did Joyce ever have a comment that wasn’t cryptic?

Here’s what Joyce said about the man himself:

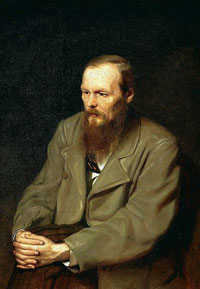

“…he [Dostoevsky] is the man more than any other who has created modern prose, and intensified it to its present-day pitch. It was his explosive power which shattered the Victorian novel with its simpering maidens and ordered commonplaces; books which were without imagination or violence”.

Less cryptic (possibly).

Is violence necessary to make a novel worthy? I wonder this about modern movies. It is hard to find well-done movies (not the Hollywood blockbusters but small, well-crafted movies) without violence.

To get your question, Dennis, I do not see how Alyona Ivanova’s murder is, in any way, justifiable. It may be rationalizable (is that a word?), but not justifiable. She may not be a model person, but she has done nothing to deserve a death penalty (at least, nothing we’ve been aware of). It seems she certainly has mistreated her sister, but (to be frankly cruel), in a manner that seems to be somewhat acceptable in that world.

This gets back to the discussion between the student and the officer. The student asks, “wouldn’t thousands of good deeds make up for one tiny, little crime?” The officer comments, “[o]f course, she does not deserve to be alive.” When is murder, any murder, only a “tiny, little crime?” When does one have to “deserve to be alive”? Characterizing both life and the deliberate taking of life as so trivial is part of Dostoevsky’s brilliantly subtle manner of bringing us into this awful immorality. What I am still trying to figure out is whether he is concerned about curing the immorality or has resigned himself to accepting it (or is he forcing us to make that very decision?)

Hi, folks. I just caught up to everyone. R. is starving to death, after all, and so are lots of other people he runs into. His sister is days away from legally prostituting herself to support him and M’s daughter is already out working the street. His mother is going into debt for him. And he has no rent money, no food, no more university, no future prospects other than what his sister can muster based on her marriage. I always understood the murders to be R’s desperate act, which catapults him into an “unreal” situation. The widow and her sister were victims of opportunity rather than chosen as not worth to live. Who else does R. frequent with such ready cash just as he is ripe to go for it?

Anyone else notice the dream sequence bringing to mind the practice of lucid dreaming http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lucid_dream : “…Marquis d’Hervey de Saint-Denys was probably the first person to argue that it is possible for anyone to learn to dream consciously. In 1867, he published his book Les Reves et les moyens de les diriger; observations pratiques (“Dreams and How to Guide them; Practical Observations”), in which he documented more than twenty years of his own research into dreams…”

Funny you should bring up the topic of “lucid dreaming.” From today’s New York Times, and an article on Jared L. Laughner:

A quote from Brenna Castle, 21, a friend of Laughner’s in junior and senior high school:

“And then there was that fascination with dreams. Ms. Castle acknowledged that in high school, she too developed an interest in analyzing her dreams. But Jared’s interest was much deeper.

‘It started off with dream interpretation, but then he delved into the idea of accessing different parts of your mind and trying to control your entire brain at all times,’ she said. ‘He was trouble that we only use part of our brain, and he thought that he could unlock his entire brain, and he thought that he could unlock his entire brain through lucid dreaming.’

With ‘lucid dreaming,’ the dreamer supposedly becomes aware that he or she is dreaming and then is sable to control those dreams. George Osler IV, the father of one of Jared’s former friends, said his son explained the notion to him this way: ‘You can fly. You can experience all kinds of things that you can’t experience in reality.’

But Mr. Osler worried about the healthiness of this boyhood obsession, particularly the notion that ‘This is all not real.’

Gradually, friends and acquaintances say, there, came a detachment from the waking world — a strangeness that made others uncomfortable.

Mr. Laughner unnerved one parent, Mr. Osler, by smiling when there wasn’t anything to smile about. He puzzled another parent, Ms. Montanaro, by reading aloud a short story he had written, about angels and the end of the world, that she found strange and incomprehensible. And he rattled Breanna Castle, his friend, by making a video that featured a gas station, traffic, and his incoherent mumbles.

‘The more people became shocked and worried about him, the more withdrawn he got.'”

Not to draw too explicit a parallel, but…”Do you like street singing?…”